After ten consecutive rate hikes, the Fed decided on wednesday to pause its monetary tightening cycle. An expected decision.

The US central bank indicated that rate cuts were unlikely in 2023, while reaffirming its inflation target of 2%. However, it has announced that two further rate hikes of 25 basis points are expected by the end of the year.

By threatening to raise rates again, the Fed is "keeping up the pressure" and hoping to quell any resurgence in inflation, which it is having a decidedly difficult time taming.

This pause comes at a time when we are seeing the first significant effects of higher rates on the economy.

We have already discussed the impact of rate hikes on banks. As I wrote in my last article: "The real estate crisis of 2023 is much less visible. It can be seen in the banks' balance sheets, via the depreciation in the level of return on securities in relation to the value of the assets held, but not in house prices."

These depreciations translate into losses on securities backed by bond products, and could have worsened banks' balance sheets had it not been for the Fed's intervention last March.

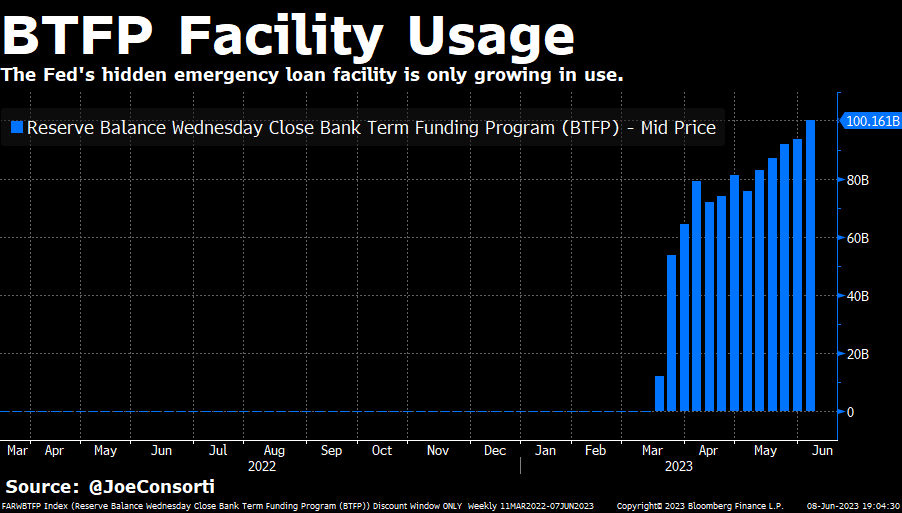

Banks are now transferring losses on impaired securities using the Bank Term Funding Program (BRFP), the rescue plan set up after the Silicon Valley collapse. Losses are being transferred to the Fed's balance sheet at an accelerated pace:

This financing program brought bank failures to a screeching halt and, above all, averted the threat of a liquidity crisis: the window allowing banks to exchange a downgraded bond product for freshly printed cash at its purchase value (and not its market value) helped the markets to recover.

The Fed has saved the banks again, but will it be able to save the other victims of rising interest rates?

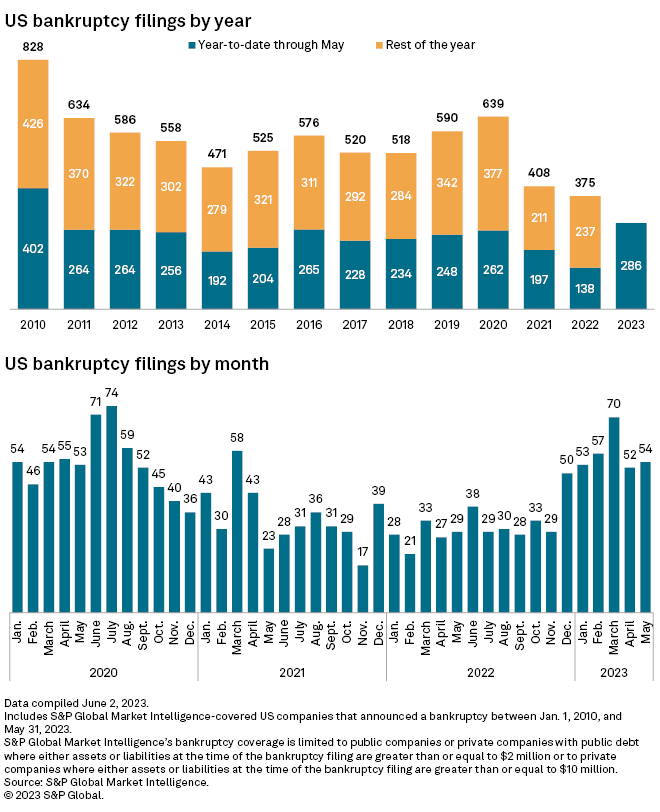

The number of US corporate bankruptcies has risen sharply at the start of the year:

CNN Business reports that manufacturers are facing falling demand and a gloomy outlook. The US and the eurozone are contracting. China's industry is temporarily improving, but exports are falling. Global optimism is at an all-time low. Rising interest rates are depressing consumption. Most industrialists expect a mild recession in the US, but a deeper one in Europe. The eurozone's entry into recession was confirmed this week.

Caution is therefore the order of the day for economic players, and this is translating into layoffs and lower revenues. Manufacturers face a number of challenges: they have to keep their employees, while operating in a weak economy and unfavorable business climate. The outlook is bleak, with a sharp drop in export orders.

But it's the real estate sector that's increasingly worrying.

More than eight million Americans are behind with their rent payments. This particularly concerns the most indebted households, unable to cope with rising consumer credit repayment costs.

Unsurprisingly, the consequences of higher rates are beginning to impact businesses and the poorest.

If the Fed has saved the banks, it is unlikely to be so quick to do the same with those hardest hit by its monetary policy. That's not its role, nor its mission. Only the federal government could intervene, but its room for manoeuvre is reduced by an ever-widening deficit. As financing the current debt is already very complicated, it is difficult to envisage a new plan to support businesses and the poorest households. Could the Fed intervene again to help the Treasury monetize part of its debt?

On this very point, Jerome Powell cast a pall over the Fed meeting. A journalist asked the burning question: "Who is going to finance US public debt?" The Fed Chairman's response was blunt: "That's none of my business!". In other words, as long as he's head of the Fed, Powell won't be launching a new debt buyback program to help absorb the avalanche of Treasuries the US government is about to issue. Warning shot or bluff?

In the face of such clear-cut rhetoric, the dollar should logically rally. The U.S. currency absolutely must stage a significant rebound to validate the trend change begun in February. But for the moment, this significant rebound is far from being confirmed:

In anticipation of a sharp rebound in the dollar, the gold price is logically continuing its consolidation trend, albeit without breaking any major supports:

With inflation falling and no short-term recession forecast, gold should have fallen much more violently. Four billion was spent shorting 20,000 futures contracts in the eight minutes following the Fed's decision. This represents 2% of world production sold in just a few minutes on the futures market. We're going to have to spend a lot more to push gold significantly lower!

The price of silver also failed to correct as usual. In fact, the very firm tones of previous Fed statements have tended to have a greater impact on the gray metal:

The dollar would have to bounce back strongly to see a real correction in precious metals. A correction that bears committed to this speculative bet has been impatiently awaiting for several months.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.